For decades, scientists have puzzled over one of medicine’s most confounding mysteries: Why doesn’t our immune system recognize and fight cancer the way it does other diseases, like the common cold?

As it turns out, the answer to that question can be traced to a series of tricks that cancer has developed to turn off normal immune responses – tricks that scientists have only recently discovered and learned to defeat. The result is what many are calling cancer’s “penicillin moment”, a revolutionary discovery in our understanding of cancer and how

to beat it.

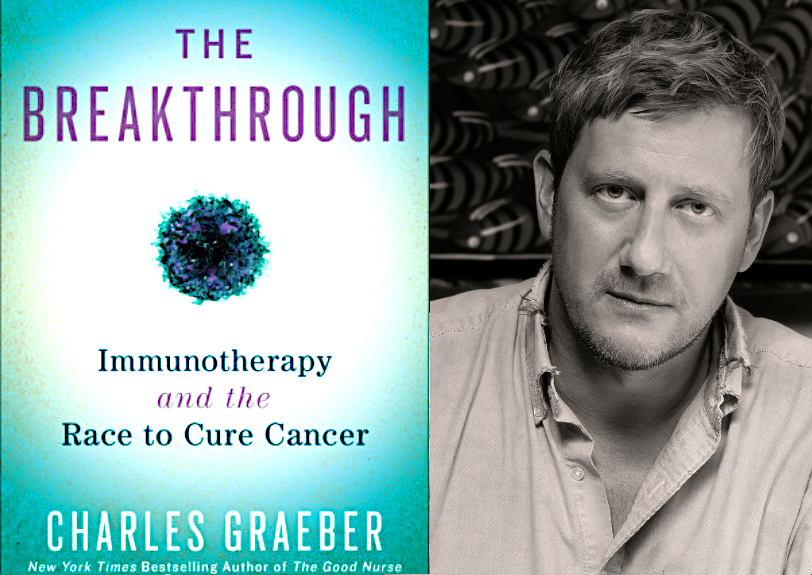

In The Breakthrough, New York Times best-selling author of The Good Nurse

Charles Graeber guides listeners through the revolutionary scientific research bringing immunotherapy out of the realm of the miraculous and into the forefront of 21st-century medical science. As advances in the fields of cancer research and the human immune system continue to fuel a therapeutic arms race among biotech and pharmaceutical research centers around the world, the next step – harnessing the wealth of new information to create modern and more effective patient therapies – is unfolding at an unprecedented pace, rapidly redefining our relationship with this all-too-human disease.

Groundbreaking, riveting, and expertly told, The Breakthrough is the story of the

game-changing scientific discoveries that unleash our natural ability to recognize and defeat cancer, as told through the experiences of the patients, physicians, and cancer immunotherapy researchers who are on the front lines. This is the incredible true story

of the race to find a cure, a dispatch from the life-changing world of modern oncological science, and a brave new chapter in medical history.

Every year 17 million people are diagnosed with cancer across the world. A further 10 million people die of cancer-related deaths every year. As one notable oncologist politely put it, you’re more likely to get cancer than you are to get married. But those days of trembling at hearing the word cancer or equating it to a death sentence is over.

The Cure For Cancer Has Arrived

By Charles Graeber – Bing video

Traditionally the solution to eliminating this ghastly mutated foe was to either

cut it or burn it out with traditional techniques like chemotherapy or surgery. But a new dawn is upon us and it’s called immunotherapy. Immunotherapy represents a new class of specialized assassin drugs that, to put it simply, allows our immune system to see cancer operating in broad daylight, where it was once cloaked in invisibility.

Thanks to a motley group of genius scientists such as Nobel prize winners Jim Allison

and Tasuku Honjo, they have shown us that cancer can be defeated. The advent of immunotherapeutic drugs has meant that thousands of people worldwide are now finding their way into steady long-term remission. Where we go from here is up to science, but if the author of Breakthrough Charles Graeber would have us believe we can now dream of a day where cancer becomes just another manageable disease much like the flu or even polio. Let the revolution begin.

In terms of where cancer is within the journey of the body.

Can you give us a bit of background and perhaps a bit of context to the disease?

Well, cancer is part of us, it’s an inseparable aspect of our humanity. It’s a mutation that works, and in a sense, that’s us as well. The whole notion of evolution is that mistakes lead to differential reproductive success and some of that differential reproductive success happens on a cellular level, and that’s a tumour. So this is something that’s plagued us since the very beginning. Usually, because we know our cells are rolling the dice over and over again.

In a sense, we were always busy dealing with microbes and the basic issues of survival; you were more likely to get eaten by a tiger or destroyed by microbes than you were to develop a tumour. It’s a luxury to be able to worry about cancer, but now it is, of course, our second biggest killer. The main observation made by physicians was that for as long as we’ve had cancer, it was always a disease that was symptomless, that is until it crowded out the other organs. It was something that was unlike any other condition. It’s different when you have a cold or flu. With cancer, there is no inflammation, no fever, not even a runny nose. And there is nothing to be done about it. Traditionally, the only treatment for cancer has been to cut it out or death.

This leads to the second observation by historians and physicians that occasionally cancer would burst through the skin especially in a crab-like shape, which the writer Siddhartha Mukherjee describes very well in his book The Emperor of All Maladies. It would lead to this infection, and this infection would somehow suddenly reverse the course of the disease to what they called spontaneous remission.

“The physicians and the researchers I speak to believe that this will render cancer a manageable disease if we don’t cure outright for the vast majority of people within our lifetime.” – Charles Graeber

So to dig a little deeper, what does a tumour get out of differential reproductive success? Because essentially if a tumour is successful it kills

the body and then the tumour doesn’t survive anymore. So what is in it for a tumour to grow there in the first place?

That’s a great question. And this is a fun one to wrestle with.

Within the smaller picture, there’s always a sense that with evolution the point of it is that it had a direction. I think it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of evolution. It’s merely a matter of being able to reproduce yourself and pass on whatever that environment may be. In this case, it doesn’t apply because it’s not an organism, it doesn’t affect us as such. It’s a byproduct of a random mutation, and sometimes that happens on a genetic level which concerns us as a species.

Usually when the cells reproduce or when they divide they make mistakes and are cleaned up pretty quickly, or they are induced to kill themselves which is called apoptosis. It’s just sort of spring cleaning in the body, and we shed the equivalent of our body weight every year in these cells which is why our apartments are so dusty even though we’d like to think it was something else.

So, it’s 2018, and we’re at a pivotal point in the world of cancer.

A breakthrough has been made, is this the revolution we’ve all been waiting for. Is the cut and burn era over?

You have to be so careful with this question because the idea of raising false hope is cruel. We’ve seen this time and time again, where there have been breakthroughs, but it becomes one of the most shopworn headlines out there. The short answer is yes, this is the breakthrough. This is a penicillin moment for this disease, which is to say we have fundamentally changed our understanding of the disease and of ourselves and how our immune system interacts or has forever failed to interact with cancer.

We understand that cancer takes advantage of the safety mechanism built into our immune system. Cancer uses a secret handshake to shut down the immune system

and to say “I’m cool, I’m a normal body cell, don’t attack me.” We count on these secret handshakes or checkpoints for the body not to be attacking ourselves all the time, to not be in a constant state of autoimmunity. The most dangerous thing in our bodies usually is our defenses, and that has evolved over 500 million years, and they’re really good. And when they go wrong, it’s terrible.

The safety built into them is necessary. We now know cancer takes advantage of those safety checks and now we know we can block that. That understanding has been sought after for well over one hundred and fifty years. It’s something that has puzzled humanity forever. And it was only understood recently.

So this is all fundamental to reimagining what is possible, and already the question is

‘Can we cure cancer or the 200 some diseases we know as cancer?’ And the answer is we already have cured cancer. We haven’t cured everybody but we’ve cured it in certain types of cancers and the subset of patients, that equates to tens if not hundreds of thousands of people.

The physicians and the researchers I speak to believe that this will render cancer a manageable disease if we don’t cure outright for the vast majority of people within our lifetime.

A tray containing cancer cells sitting on an optical microscope in the Nanomedicine Lab at UCL’s School of Pharmacy in London. REUTERS/Suzanne Plunkett

Essentially you’re saying these drugs called checkpoint inhibitors basically allow the immune system to function as normal and kill a tumour. But are you also saying that over time these checkpoint inhibitor drugs will become not only more intelligent but a lot more precise and they’ll be able to do a much better job at removing the tumour than just carpet bombing as in the current cut and burn process?

Any successful cancer already depends upon the immune system to be successful.

You can cut out the vast number of tumors or you can starve it, you can use any of the techniques that we’ve had such as cut it out, poison it and burn it. But techniques of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation are essentially a game of chicken where you hope that you kill the disease before you kill the host, being the patient.

What you’re doing is hoping to change the odds of the fight with the immune system but it has to be an awakened immune system to chase down every last cell. No drug can do it. Cancer mutates, it continues to change. But a drug does not change and we see this all the time with remissions where people are ok for a while and then the disease comes roaring back. This is because the treatments aren’t adaptable and flexible, they don’t dance and the immune system dances. So in a sense, it’s the only path that will work.

These checkpoint discoveries are tantamount to finding invisible breaks that were initially put on the cells that fight our diseases, which are the immune killer cells, the T-cell.

The problem is that the anti- CTL4-A drug which came first acted indiscriminately. It was similar to jamming a brick under the brake pedal. So, for some, it can be a rough ride, it can have a lot of toxicity because you’re creating an auto immunity. But then the anti-PD-1 drug came along which was the next checkpoint inhibitor drug, but this acts as a more precise checkpoint that can be targeted which changed everything.

Cancer therapy was really a science in disgrace. It was discredited underfunded

and it was the laughingstock of the cancer community because everyone knew that the immune system could not see cancer. There was no point in going in that direction.

Even the few immune therapists out there could not point out what was happening,

even though they guessed what was going in. Nothing worked in patients until extremely recently and the big change is that now we know that’s absolutely untrue.

Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Emperor of All Maladies does not mention cancer immunotherapy once and it’s because he is a classically trained chemotherapist/oncologist and then they were trained against it.

That’s why people refer to this as a penicillin moment. It wasn’t just the penicillin

which saved millions of lives – it was the understanding that these drugs could block these little critters that had plagued us for so long. That we could actually control the most basic diseases with a whole class of drugs that fundamentally changed our lives.

Source: National Cancer Institute

To be honest, reading your book, I was just amazed at how intelligent

cancer really is, its process of hiding in front of the immune system is quite ingenious. We’ve been underestimating the depth of it for so long.

Well, part of that is a failure of imagination and part of it is simply that we didn’t

really have the science to understand what it is. I’d say it’s pretty much the equivalent to exploring the deep ocean in our own bloodstream.

One of my concerns is that once we’ve managed cancer or nearly cured it and it will lead to a more vicious mutation, if cancer is so intelligent surely it will come up with another sophisticated way to attack the system that will evade us?

Yes, our immune system is cancer or rather shall we say they train in the same gym, they were brought up together, they are one and the same. This is not a disease or a strain of flu, it’s really a matter of allowing our immune system to dance unshackled and also we’re now able to apply other understandings of cancer to other approaches.

We can now make a Robocop version of the T cell.

Nobel prize-winning immunologist Jim Allison. Photo: LeAnn Mueller

Must Watch: Pluto TV – Jim Allison: Breakthrough

Synopsis:

Jim Allison: Breakthrough is the astounding, true story of one warm-hearted,

stubborn man’s visionary quest to find a cure for cancer.

Today, Jim Allison is a name to be reckoned with throughout the scientific world —

a 2018 Nobel Prize winner for discovering the immune system’s role in defeating cancer — but for decades he waged a lonely struggle against the skepticism of the medical establishment and the resistance of Big Pharma.

Jim Allison: Breakthrough takes us into the inspiring and dramatic world of cutting-edge medicine, and into the heart of a true American pioneer, in a film that is both emotionally compelling and deeply entertaining.

James Allison, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine, was born on August 7, 1948 in a tiny South Texas town called Alice. Named for the daughter of the legendary King Ranch owner, Alice has boasting rights as birthplace of a second Nobel winner, Robert F. Curl, Jr., who took the honor for chemistry in 1996. It is also where Tejano, a unique Tex-Mex musical genre, took root in the mid-1940s. Tejano may have inspired young Jim to take up the harmonica, which he still performs at parties and events, sometimes sharing the stage with fellow Texan Willie Nelson.

Allison’s father, Albert, was a physician and his mother, Constance, a homemaker and “positive influence” who tragically died of lymphoma when he was eleven years old.

There were 2 older brothers, Murphy and Mike. Life was difficult for Jim following his mother’s passing. His father, an officer in the Air Force Reserves, was often away from home, during which time he was fostered by a local family with a son about his own age.

Even as a kid, Allison displayed a yen for science. Encouraged by his parents, he toyed around with a Gilbert chemistry set, setting off little bombs in the woods behind their home. A summer in a NSF-funded science-training program deepened his interest.

After graduating from high school at sixteen, he entered the University of Texas, Austin where he would earn a B. S. Degree in microbiology (1969) and a Ph.D. in biological science (1973). He was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity.

But the fierce passion which kindled his interest in curative science, was unquestionably ignited by the early passing of his mother. His life’s path was set by the time he entered graduate school, when he convinced his PhD advisor to bring cancer study into the lab.

It was a propitious moment.

The immune system’s “T-cell” had recently been discovered. A type of white blood cell,

the T is a front-line soldier in the battle to keep us healthy, its role assigned by nature to distinguish friend from foe. Though immunology was not even a bona fide science at the time, Allison zeroed in on the immune system’s potential against cancer.

(His dissertation proposed a new approach to treating leukemia,

but decades would pass before a similar drug was patented.)

Soon after graduation, Allison began crisscrossing the country in a quest to unlock

the mysteries of the T cell. How do T cells work? How do they identify an invader?

Why can they recognize the flu virus, for example, but not cancer?

In addition to pure knowledge, he sought institutions open to innovative research –

not a simple matter in a profession tending toward caution and rigidity.

His first stop was Scripps Clinic & Research Foundation in San Diego (1974-77)

where he did postdoctoral work.

Married by now to the former Malinda Bell, the couple often joined other Texas

ex-patriots at the port city’s Stingaree bar. He fondly remembers one night playing his harmonica until the wee hours with Willie Nelson and his band. “I didn’t have to buy a beer for a couple of years after that,” he recalls.

LOVE THIS VIDEO: TCU “We Fight Back” Flash Mob for Komen

That is called CAR T-Cell therapy, right? (A type of treatment in which a patient’s

T cells (a type of immune system cell) are changed in the laboratory so they will attack cancer cells.)

Yes, that spin-off is based on a new understanding of the immune system.

But you’re right, we’ve been underestimating the disease for a long time and failing, but we didn’t have much of a choice, it beat us every time.

What I found interesting was that in the end, the best thing you could do was to personify it and to give it some Majesty, hence Siddartha Mukherjee’s famous book, the Emperor of All Maladies if you will, so that you were vanquished by a worthy foe. That was the best we could offer, a noble death and now we’ve got other options.

“It’s really a matter of allowing our immune system to dance unshackled.”

There are currently as far as I understand almost a thousand immunotherapeutic drugs being tested by more than half a million patients. and another thousand drugs in the preclinical stage. Where do we go from here? What happens to all the people reading this that have been touched by cancer that wants to understand more?

Well, the fight is on, and in a sense, it’s on for the first time. And that’s exciting.

The excitement needs to be tempered a bit though. There was this initial flush of enthusiasm and rightly so because some major successes happened. But we could use another breakthrough. We’re awaiting results on a weekly basis.

We used to have medical journals with updates on cancer only intermittently

now have new cancer immunotherapy updates on a weekly or bi-weekly basis.

It will be exciting to see what comes off first, all the combinations that are being tried

and those are just starting to tick out. Personalized vaccines are hugely exciting, which is basically where you go and typify your cancer that relates to your immune system.

You then figure out the version of a drug that’s going to hurt you the least and cancer the most. That’s science fiction stuff that’s now the clinical trials phase and continue to.

One of the hot areas right now is based on biomarkers and various means to figure out who will best benefit from what.

But in reality, it’s the economic toxicity that kills more people than anything.

We need to allow patients to be able to make better choices faster, based on what they need because if the drug works in just 40% of people, we’re just wasting your valuable time.

But we also see for the first time an influx of talent from fields beyond the very narrow crosshairs of cancer and immunity. And thinkers from outside that space are coming into this space. It is sort of a sort of medical renaissance.

To temper this excitement down, some in the field have noted that Immunotherapy works on roughly 20 percent of people and that they have a variable survival benefit. Some patients get to live long and productive lives, but many don’t. That it works well in some cancers and not at all for others and we are still finding ways to distinguish the two.

I‘m very very cautious. It’s a subset of patients and a subset of cancers. We’ve not arrived at a full and total cure. The door in a sense has only just opened, and there is a great hope that this will amount to a cure and treatment for a larger and larger group of patients. The notion of a total cure for all cancer is obviously the goal. I also think the idea that it’s all or nothing is a false goal.

It’s certainly not the way we treat mortality. The reality is, what you get with these is an immediate therapeutic response which is fundamentally different than the extra months

of life often that were given from front-line therapies.

What we’re looking at now is either it works, or it doesn’t.

There are remissions – and it doesn’t work in all patients. But for those whom it does work that is 20 percent of a hundred million people. It’s not right to just throw away those numbers. It’s 20 per cent success rate in some cancers, it’s 40 per cent in others, and it’s closer to 98 per cent in certain forms of childhood leukemia.

“We’ve blown open a whole door to a new wave of understanding diseases and treating it as so much of that.” – Charles Graeber

Lastly, do you think immunotherapy could be deployed to fight other diseases other than cancer as well? I’m aware of the AIDS epidemic and its relation to the immune system, and how it could have potentially been deployed early on had they the means.

How do you see that happening?

Yes, that’s a fascinating aspect of this, we’ve blown open a whole door to a new wave of understanding diseases and treating it as so much of that. It’s interesting you know so much of cancer immunotherapy came out of the AIDS epidemic.

Many of the researchers had experience with the failure of immunity.

Now that we know cancer therapy was considered a fringe science or some alternative treatment as did other “alternative therapies” which were looked at sideways by the mainstream scientific establishment. We’re now understanding the role the immune system has in diseases like schizophrenia. It looks like diabetes and Alzheimer’s. We always thought of these as being outside diseases that perhaps the immune system failed to pick up on that.

We’ve failed to realize that perhaps we need to treat the immune system

rather than the disease. And the patient rather than the disease if you will and that that’s the breakthrough. It’s changed the horizons for a whole generation of scientists and

for us of course as humans.

The Breakthrough: immunotherapy and the race to cure cancer is out now through Scribe.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity purposes