Go to Patient Version

ON THIS PAGE

Overview

General Information

History

Laboratory/Animal/Preclinical Studies

Human/Clinical Studies

Adverse Effects

Summary of the Evidence for Cannabis and Cannabinoids

Latest Updates to This Summary (08/03/2023)

About This PDQ Summary

Overview

Cannabis and Cancer – Search Videos (bing.com)

This cancer information summary provides an overview of the use of Cannabis and its components as a treatment for people with cancer-related symptoms caused by the disease itself or its treatment.

This summary contains the following key information:

Cannabis has been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years.

By federal law, the possession of Cannabis is illegal in the United States, except within approved research settings; however, a growing number of states, territories, and the District of Columbia have enacted laws to legalize its medical and/or recreational use.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved Cannabis as a treatment for cancer or any other medical condition.

Chemical components of Cannabis, called cannabinoids, activate specific receptors throughout the body to produce pharmacological effects, particularly in the central nervous system and the immune system.

Commercially available cannabinoids, such as dronabinol and nabilone, are approved drugs for the treatment of cancer-related side effects.

Cannabinoids may have benefits in the treatment of cancer-related side effects.

Many of the medical and scientific terms used in this summary are hypertext linked (at first use in each section) to the NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms, which is oriented toward non-experts. When a linked term is clicked, a definition will appear in a separate window.

Reference citations in some PDQ cancer information summaries may include links to external websites that are operated by individuals or organizations for the purpose of marketing or advocating the use of specific treatments or products. These reference citations are included for informational purposes only. Their inclusion should not be viewed as an endorsement of the content of the websites, or of any treatment or product, by the PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board or the National Cancer Institute.

General Information

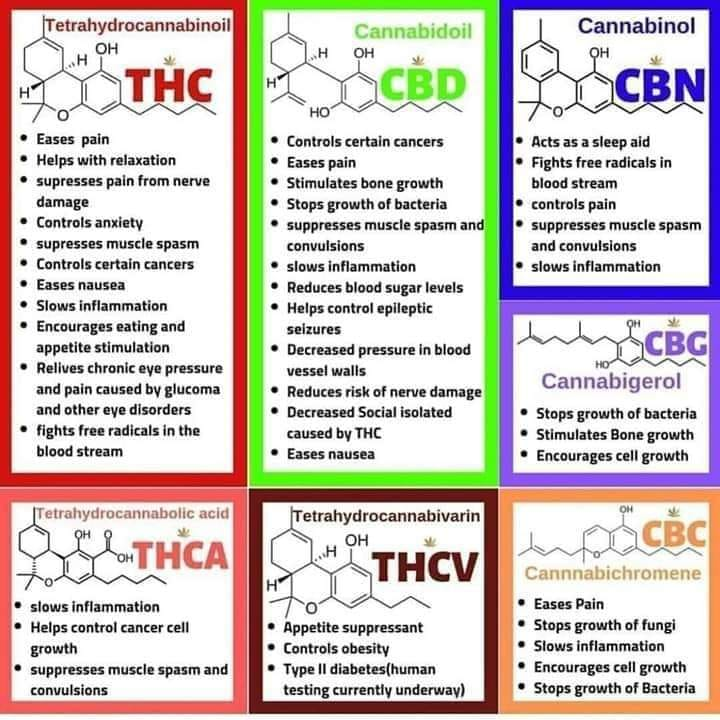

Cannabis, also known as marijuana, originated in Central Asia but is grown worldwide today. In the United States, it is a controlled substance and is classified as a Schedule I agent (a drug with a high potential for abuse, and no currently accepted medical use). The Cannabis plant produces a resin containing 21-carbon terpenophenolic compounds called cannabinoids, in addition to other compounds found in plants, such as terpenes and flavonoids. The highest concentration of cannabinoids is found in the female flowers of the plant.[1] Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the main psychoactive cannabinoid, but over 100 other cannabinoids have been reported to be present in the plant. Cannabidiol (CBD) does not produce the characteristic altered consciousness associated with Cannabis. It is felt to have potential therapeutic effectiveness and has recently been approved in the form of the pharmaceutical Epidiolex for the treatment of refractory seizure disorders in children. Other cannabinoids that are being investigated for potential medical benefits include cannabinol (CBN), cannabigerol (CBG), and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV).

Clinical trials conducted on medicinal Cannabis are limited. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved the use of Cannabis as a treatment for any medical condition, although both isolated THC and CBD pharmaceuticals are licensed and approved. To conduct clinical drug research with botanical Cannabis in the United States, researchers must file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA, obtain a Schedule I license from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and obtain approval from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In the 2018 United States Farm Bill, the term hemp is used to describe cultivars of the Cannabis species that contain less than 0.3% THC. Hemp oil or CBD oil are products manufactured from extracts of industrial hemp (i.e., low-THC cannabis cultivars), whereas hemp seed oil is an edible fatty oil that is essentially cannabinoid-free (see Table 1). Some products contain other botanical extracts and/or over-the-counter analgesics. These products are readily available as oral and topical tinctures or other formulations often advertised for pain management and other purposes. Hemp products containing less than 0.3% of delta-9-THC are not scheduled drugs and could be considered as Farm Bill compliant. Hemp is not a controlled substance; however, CBD is a controlled substance.

Table 1. Medicinal Cannabis Products—Guide to Terminology

Name/Material

Constituents/Composition

CBD = cannabidiol; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

Cannabis species, including C. sativa

Cannabinoids; also terpenoids and flavonoids

• Hemp (aka industrial hemp)

Low Δ9-THC (<0.3%); high CBD

• Marijuana/marihuana

High Δ9-THC (>0.3%); low CBD

Nabiximols (trade name: Sativex)

Mixture of ethanol extracts of Cannabis species; contains Δ9-THC and CBD in a 1:1 ratio

Hemp oil/CBD oil

Solution of a solvent extract from Cannabis flowers and/or leaves dissolved in an edible oil; typically contains 1%–5% CBD

Hemp seed oil

Edible, fatty oil produced from Cannabis seeds; contains no or only traces of cannabinoids

Dronabinol (trade names: Marinol and Syndros)

Synthetic Δ9-THC

Nabilone (trade names: Cesamet and Canemes)

Synthetic THC analog

Cannabidiol (trade name: Epidiolex)

Highly purified (>98%), plant-derived CBD

The potential benefits of medicinal Cannabis for people living with cancer include the following:[2]

Antiemetic effects.

Appetite stimulation.

Pain relief.

Improved sleep.

Although few relevant surveys of practice patterns exist, it appears that physicians caring for patients with cancer in the United States who recommend medicinal Cannabis do so predominantly for symptom management.[3] A growing number of pediatric patients are seeking symptom relief with Cannabis or cannabinoid treatment, although studies are limited.[4] The American Academy of PediatricsExit Disclaimer has not endorsed Cannabis and cannabinoid use because of concerns about brain development.

This summary will review the role of Cannabis and the cannabinoids in the treatment of people with cancer and disease-related or treatment-related side effects. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) hosted a virtual meeting, the NCI Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Cancer Research Symposium, on December 15–18, 2020. The seven sessions are summarized in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute MonographsExit Disclaimer and contain basic science and clinical information as well as a summary of the barriers to conducting Cannabis research.[5–11]

References

Adams IB, Martin BR: Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 91 (11): 1585-614, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

Abrams DI: Integrating cannabis into clinical cancer care. Curr Oncol 23 (2): S8-S14, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

Doblin RE, Kleiman MA: Marijuana as antiemetic medicine: a survey of oncologists’ experiences and attitudes. J Clin Oncol 9 (7): 1314-9, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

Sallan SE, Cronin C, Zelen M, et al.: Antiemetics in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer: a randomized comparison of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and prochlorperazine. N Engl J Med 302 (3): 135-8, 1980. [PUBMED Abstract]

Ellison GL, Alejandro Salicrup L, Freedman AN, et al.: The National Cancer Institute and Cannabis and Cannabinoids Research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 35-38, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

Sexton M, Garcia JM, Jatoi A, et al.: The Management of Cancer Symptoms and Treatment-Induced Side Effects With Cannabis or Cannabinoids. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 86-98, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cooper ZD, Abrams DI, Gust S, et al.: Challenges for Clinical Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 114-122, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

Braun IM, Abrams DI, Blansky SE, et al.: Cannabis and the Cancer Patient. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 68-77, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

Ward SJ, Lichtman AH, Piomelli D, et al.: Cannabinoids and Cancer Chemotherapy-Associated Adverse Effects. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 78-85, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

McAllister SD, Abood ME, Califano J, et al.: Cannabinoid Cancer Biology and Prevention. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 99-106, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

Abrams DI, Velasco G, Twelves C, et al.: Cancer Treatment: Preclinical & Clinical. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 107-113, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

History

Cannabis use for medicinal purposes dates back at least 3,000 years.[1–5] It was introduced into Western medicine in 1839 by W.B. O’Shaughnessy, a surgeon who learned of its medicinal properties while working in India for the British East India Company. Its use was promoted for reported analgesic, sedative, anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, and anticonvulsant effects.

In 1937, the U.S. Treasury Department introduced the Marihuana Tax Act. This Act imposed a levy of $1 per ounce for medicinal use of Cannabis and $100 per ounce for nonmedical use. Physicians in the United States were the principal opponents of the Act. The American Medical Association (AMA) opposed the Act because physicians were required to pay a special tax for prescribing Cannabis, use special order forms to procure it, and keep special records concerning its professional use.

In addition, the AMA believed that objective evidence that Cannabis was harmful was lacking and that passage of the Act would impede further research into its medicinal worth.[6] In 1942, Cannabis was removed from the U.S. Pharmacopoeia because of persistent concerns about its potential to cause harm.[2,3] Recently, there has been renewed interest in Cannabis by the U.S. Pharmacopeia.[7]

In 1951, Congress passed the Boggs Act, which for the first time included Cannabis with narcotic drugs. In 1970, with the passage of the Controlled Substances Act, marijuana was classified by Congress as a Schedule I drug. Drugs in Schedule I are distinguished as having no currently accepted medicinal use in the United States. Other Schedule I substances include heroin, LSD, mescaline, and methaqualone.

Despite its designation as having no medicinal use, Cannabis was distributed by the U.S. government to patients on a case-by-case basis under the Compassionate Use Investigational New Drug program established in 1978. Distribution of Cannabis through this program was closed to new patients in 1992.[1–4] Although federal law prohibits the use of Cannabis, Figure 1 below shows the states and territories that have legalized Cannabis use for medical purposes. Additional states have legalized only one ingredient in Cannabis, such as cannabidiol (CBD), and are not included in the map. Some medical marijuana laws are broader than others, and there is state-to-state variation in the types of medical conditions for which treatment is allowed.[8]

ENLARGE

Figure 1. A map showing the U.S. states and territories that have approved the

Figure 1. A map showing the U.S. states and territories that have approved the medical use of Cannabis. Last updated: 10/14/2021The main psychoactive constituent of Cannabis was identified as delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).

In 1986, an isomer of synthetic delta-9-THC in sesame oil was licensed and approved for the treatment of chemotherapy-associated nausea and vomiting under the generic name dronabinol. Clinical trials determined that dronabinol was as effective as or better than other antiemetic agents available at the time.[9] Dronabinol was also studied for its ability to stimulate weight gain in patients with AIDS in the late 1980s. Thus, the indications were expanded to include treatment of anorexia associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection in 1992. Clinical trial results showed no statistically significant weight gain, although patients reported an improvement in appetite.[10,11] Another important cannabinoid found in Cannabis is CBD.[12] This is a nonpsychoactive cannabinoid, which is an analog of THC.

In recent decades, the neurobiology of cannabinoids has been analyzed.[13–16] The first cannabinoid receptor, CB1, was identified in the brain in 1988. A second cannabinoid receptor, CB2, was identified in 1993. The highest expression of CB2 receptors is located on B lymphocytes and natural killer cells, suggesting a possible role in immunity. Endogenous cannabinoids (endocannabinoids) have been identified and appear to have a role in pain modulation, control of movement, feeding behavior, mood, bone growth, inflammation, neuroprotection, and memory.[17]

Nabiximols (Sativex), a Cannabis extract with a 1:1 ratio of THC:CBD, is approved in Canada (under the Notice of Compliance with Conditions) for symptomatic relief of pain in advanced cancer and multiple sclerosis.[18] Nabiximols is an herbal preparation containing a defined quantity of specific cannabinoids formulated for oromucosal spray administration with potential analgesic activity. Nabiximols contains extracts from two Cannabis plant varieties. The extracts mixture is standardized to the concentrations of the psychoactive delta-9-THC and the non psychoactive CBD. The preparation also contains other, more minor cannabinoids, flavonoids, and terpenoids.[19] Canada, New Zealand, and most countries in western Europe also approve nabiximols for spasticity of multiple sclerosis, a common symptom that may include muscle stiffness, reduced mobility, and pain, and for which existing therapy is unsatisfactory.

References

Abel EL: Marihuana, The First Twelve Thousand Years. Plenum Press, 1980. Also available onlineExit Disclaimer. Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Joy JE, Watson SJ, Benson JA, eds.: Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base. National Academy Press, 1999. Also available onlineExit Disclaimer. Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Mack A, Joy J: Marijuana As Medicine? The Science Beyond the Controversy. National Academy Press, 2001. Also available onlineExit Disclaimer. Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Booth M: Cannabis: A History. St Martin’s Press, 2003.

Russo EB, Jiang HE, Li X, et al.: Phytochemical and genetic analyses of ancient cannabis from Central Asia. J Exp Bot 59 (15): 4171-82, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

Schaffer Library of Drug Policy: The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937: Taxation of Marihuana. Washington, DC: House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, 1937. Available onlineExit Disclaimer. Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Sarma ND, Waye A, ElSohly MA, et al.: Cannabis Inflorescence for Medical Purposes: USP Considerations for Quality Attributes. J Nat Prod 83 (4): 1334-1351, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. The National Academies Press, 2017.

Sallan SE, Zinberg NE, Frei E: Antiemetic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 293 (16): 795-7, 1975. [PUBMED Abstract]

Gorter R, Seefried M, Volberding P: Dronabinol effects on weight in patients with HIV infection. AIDS 6 (1): 127, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al.: Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage 10 (2): 89-97, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

Adams R, Hunt M, Clark JH: Structure of cannabidiol: a product isolated from the marihuana extract of Minnesota wild hemp. J Am Chem Soc 62 (1): 196-200, 1940. Also available onlineExit Disclaimer. Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Devane WA, Dysarz FA, Johnson MR, et al.: Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 34 (5): 605-13, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, et al.: Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258 (5090): 1946-9, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, et al.: International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB₁ and CB₂. Pharmacol Rev 62 (4): 588-631, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

Felder CC, Glass M: Cannabinoid receptors and their endogenous agonists. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 38: 179-200, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G: The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 58 (3): 389-462, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

Howard P, Twycross R, Shuster J, et al.: Cannabinoids. J Pain Symptom Manage 46 (1): 142-9, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

Nabiximols. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2009. Available online. Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Laboratory/Animal/Preclinical Studies

In This Section

Antitumor Effects

Antiemetic Effects

Appetite Stimulation

Analgesia

Anxiety and Sleep

Cannabinoids are a group of 21-carbon–containing terpenophenolic compounds produced uniquely by Cannabis species (e.g., Cannabis sativa L.).[1,2] These plant-derived compounds may be referred to as phytocannabinoids. Although delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the primary psychoactive ingredient, other known compounds with biological activity are cannabinol, cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene, cannabigerol, tetrahydrocannabivarin, and delta-8-THC. CBD, in particular, is thought to have significant analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and anxiolytic activity without the psychoactive effect (high) of delta-9-THC.

Antitumor Effects

One study in mice and rats suggested that cannabinoids may have a protective effect against the development of certain types of tumors.[3] During this 2-year study, groups of mice and rats were given various doses of THC by gavage. A dose-related decrease in the incidence of hepatic adenomama tumors and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was observed in the mice. Decreased incidences of benign tumors (polyps and adenomas) in other organs (mammary gland, uterus, pituitary, testis, and pancreas) were also noted in the rats. In another study, delta-9-THC, delta-8-THC, and cannabinol were found to inhibit the growth of Lewis lung adenocarcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo.[4] In addition, other tumors have been shown to be sensitive to cannabinoid-induced growth inhibition.[5–8]

Cannabinoids may cause antitumor effects by various mechanisms, including induction of cell death, inhibition of cell growth, and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis invasion and metastasis.[9–12] Two reviews summarize the molecular mechanisms of action of cannabinoids as antitumor agents.[13,14] Cannabinoids appear to kill tumor cells but do not affect their nontrans formed counterparts and may even protect them from cell death. For example, these compounds have been shown to induce apoptosis in glioma cells in culture and induce regression of glioma tumors in mice and rats, while they protect normal glial cells of astroglia and oligodendroglia lineages from apoptosis mediated by the CB1 receptor.[9]

The effects of delta-9-THC and a synthetic agonist of the CB2 receptor were investigated in HCC.[15] Both agents reduced the viability of HCC cells in vitro and demonstrated antitumor effects in HCC subcutaneous xenografts in nude mice. The investigations documented that the anti-HCC effects are mediated by way of the CB2 receptor. Similar to findings in glioma cells, the cannabinoids were shown to trigger cell death through stimulation of an endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway that activates autophagy and promotes apoptosis. Other investigations have confirmed that CB1 and CB2 receptors may be potential targets in non-small cell lung carcinoma [16] and breast cancer.[17]

An in vitro study of the effect of CBD on programmed cell death in breast cancer cell lines found that CBD induced programmed cell death, independent of the CB1, CB2, or vanilloid receptors. CBD inhibited the survival of both estrogen receptor–positive and estrogen receptor–negative breast cancer cell lines, inducing apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner while having little effect on non tumorigenic mammary cells.[18] Other studies have also shown the antitumor effect of cannabinoids (i.e., CBD and THC) in preclinical models of breast cancer.[19,20]

CBD has also been demonstrated to exert a chemopreventive effect in a mouse model of colon cancer.[21]

In this experimental system, azoxymethane increased premalignantt and malignant lesions in the mouse colon. Animals treated with azoxymethane and CBD concurrently were protected from developing premalignant and malignant lesions. In in vitro experiments involving colorectal cancer cell lines, the investigators found that CBD protected DNA from oxidative damage, increased endocannabinoid levels, and reduced cell proliferation. In a subsequent study, the investigators found that the antiproliferative effect of CBD was counteracted by selective CB1 but not CB2 receptor antagonists, suggesting an involvement of CB1 receptors.[22]

Another investigation into the antitumor effects of CBD examined the role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).[12] ICAM-1 expression in tumor cells has been reported to be negatively correlated with cancer metastasis. In lung cancer cell lines, CBD upregulated ICAM-1, leading to decreased cancer cell invasiveness.

In an in vivo model using severe combined immunodeficient mice, subcutaneous tumors were generated by inoculating the animals with cells from human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell lines.[23] Tumor growth was inhibited by 60% in THC-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated control mice. Tumor specimens revealed that THC had antiangiogenic and antiproliferative effects. However, research with immunocompetent murine tumor models has demonstrated immunosuppression and enhanced tumor growth in mice treated with THC.[24,25]

In addition, both plant-derived and endogenous cannabinoids have been studied for anti-inflammatory effects. A mouse study demonstrated that endogenous cannabinoid system signaling is likely to provide intrinsic protection against colonic inflammation.[26] As a result, a hypothesis that phytocannabinoids and endocannabinoids may be useful in the risk reduction and treatment of colorectal cancer has been developed.[27–30]

CBD may also enhance uptake of cytotoxic drugs into malignant cells. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 2 (TRPV2) has been shown to inhibit proliferation of human glioblastoma multiforme cells and overcome resistance to the chemotherapy agent carmustine. [31] One study showed that coadministration of THC and CBD over single-agent usage had greater antiproliferative activity in an in vitro study with multiple human glioblastoma multiforme cell lines.[32] In an in vitro model, CBD increased TRPV2 activation and increased uptake of cytotoxic drugs, leading to apoptosis of glioma cells without affecting normal human astrocytes.

This suggests that coadministration of CBD with cytotoxic agents may increase drug uptake and potentiate cell death in human glioma cells. Also, CBD together with THC may enhance the antitumor activity of classic chemotherapeutic drugs such as temozolomide in some mouse models of cancer.[13,33] A meta-analysis of 34 in vitro and in vivo studies of cannabinoids in glioma reported that all but one study confirmed that cannabinoids selectively kill tumor cells.[34]

Antiemetic Effects

Preclinical research suggests that emetic circuitry is tonically controlled by endocannabinoids. The antiemetic action of cannabinoids is believed to be mediated via interaction with the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor. CB1 receptors and 5-HT3 receptors are colocalized on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic neurons, where they have opposite effects on GABA release.[35] There also may be direct inhibition of 5-HT3 gated ion currents through non–CB1 receptor pathways. CB1 receptor antagonists have been shown to elicit emesis in the least shrew that is reversed by cannabinoid agonists.[36] The involvement of CB1 receptor in emesis prevention has been shown by the ability of CB1 antagonists to reverse the effects of THC and other synthetic cannabinoid CB1 agonists in suppressing vomiting caused by cisplatin in the house musk shrew and lithium chloride in the least shrew. In the latter model, CBD was also shown to be efficacious.[37,38]

Appetite Stimulation

Many animal studies have previously demonstrated that delta-9-THC and other cannabinoids have a stimulatory effect on appetite and increase food intake. It is believed that the endogenous cannabinoid system may serve as a regulator of feeding behavior. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide potently enhances appetite in mice.[39] Moreover, CB1 receptors in the hypothalamus may be involved in the motivational or reward aspects of eating.[40]

Analgesia

Understanding the mechanism of cannabinoid-induced analgesia has been increased through the study of cannabinoid receptors, endocannabinoids, and synthetic agonists and antagonists. Cannabinoids produce analgesia through supraspinal, spinal, and peripheral modes of action, acting on both ascending and descending pain pathways.[41] The CB1 receptor is found in both the central nervous system (CNS) and in peripheral nerve terminals. Similar to opioid receptors, increased levels of the CB1 receptor are found in regions of the brain that regulate nociceptive processing.[42] CB2 receptors, located predominantly in peripheral tissue, exist at very low levels in the CNS. With the development of receptor-specific antagonists, additional information about the roles of the receptors and endogenous cannabinoids in the modulation of pain has been obtained.[43,44]

Cannabinoids may also contribute to pain modulation through an anti-inflammatory mechanism; a CB2 effect with cannabinoids acting on mast cell receptors to attenuate the release of inflammatory agents, such as histamine and serotonin, and on keratinocytes to enhance the release of analgesic opioids has been described.[45–47] One study reported that the efficacy of synthetic CB1- and CB2-receptor agonists were comparable with the efficacy of morphine in a murine model of tumor pain.[48]

Cannabinoids have been shown to prevent chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in animal models exposed to paclitaxel, vincristine, or cisplatin.[49–51]

Anxiety and Sleep

The endocannabinoid system is believed to be centrally involved in the regulation of mood and the extinction of aversive memories. Animal studies have shown CBD to have anxiolytic properties. It was shown in rats that these anxiolytic properties are mediated through unknown mechanisms.[52] Anxiolytic effects of CBD have been shown in several animal models.[53,54]

The endocannabinoid system has also been shown to play a key role in the modulation of the sleep-waking cycle in rats.[55,56]

References

Adams IB, Martin BR: Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 91 (11): 1585-614, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

Grotenhermen F, Russo E, eds.: Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential. The Haworth Press, 2002.

National Toxicology Program: NTP toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of 1-trans-delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (CAS No. 1972-08-3) in F344 rats and B6C3F1 mice (gavage studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser 446: 1-317, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

Bifulco M, Laezza C, Pisanti S, et al.: Cannabinoids and cancer: pros and cons of an antitumour strategy. Br J Pharmacol 148 (2): 123-35, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

Sánchez C, de Ceballos ML, Gomez del Pulgar T, et al.: Inhibition of glioma growth in vivo by selective activation of the CB(2) cannabinoid receptor. Cancer Res 61 (15): 5784-9, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

McKallip RJ, Lombard C, Fisher M, et al.: Targeting CB2 cannabinoid receptors as a novel therapy to treat malignant lymphoblastic disease. Blood 100 (2): 627-34, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

Casanova ML, Blázquez C, Martínez-Palacio J, et al.: Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors. J Clin Invest 111 (1): 43-50, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

Blázquez C, González-Feria L, Alvarez L, et al.: Cannabinoids inhibit the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in gliomas. Cancer Res 64 (16): 5617-23, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

Guzmán M: Cannabinoids: potential anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer 3 (10): 745-55, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

Blázquez C, Casanova ML, Planas A, et al.: Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by cannabinoids. FASEB J 17 (3): 529-31, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

Vaccani A, Massi P, Colombo A, et al.: Cannabidiol inhibits human glioma cell migration through a cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol 144 (8): 1032-6, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

Ramer R, Bublitz K, Freimuth N, et al.: Cannabidiol inhibits lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis via intercellular adhesion molecule-1. FASEB J 26 (4): 1535-48, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Velasco G, Sánchez C, Guzmán M: Towards the use of cannabinoids as antitumour agents. Nat Rev Cancer 12 (6): 436-44, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cridge BJ, Rosengren RJ: Critical appraisal of the potential use of cannabinoids in cancer management. Cancer Manag Res 5: 301-13, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

Vara D, Salazar M, Olea-Herrero N, et al.: Anti-tumoral action of cannabinoids on hepatocellular carcinoma: role of AMPK-dependent activation of autophagy. Cell Death Differ 18 (7): 1099-111, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Preet A, Qamri Z, Nasser MW, et al.: Cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, as novel targets for inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 4 (1): 65-75, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Nasser MW, Qamri Z, Deol YS, et al.: Crosstalk between chemokine receptor CXCR4 and cannabinoid receptor CB2 in modulating breast cancer growth and invasion. PLoS One 6 (9): e23901, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Shrivastava A, Kuzontkoski PM, Groopman JE, et al.: Cannabidiol induces programmed cell death in breast cancer cells by coordinating the cross-talk between apoptosis and autophagy. Mol Cancer Ther 10 (7): 1161-72, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Caffarel MM, Andradas C, Mira E, et al.: Cannabinoids reduce ErbB2-driven breast cancer progression through Akt inhibition. Mol Cancer 9: 196, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

McAllister SD, Murase R, Christian RT, et al.: Pathways mediating the effects of cannabidiol on the reduction of breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129 (1): 37-47, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Aviello G, Romano B, Borrelli F, et al.: Chemopreventive effect of the non-psychotropic phytocannabinoid cannabidiol on experimental colon cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 90 (8): 925-34, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Romano B, Borrelli F, Pagano E, et al.: Inhibition of colon carcinogenesis by a standardized Cannabis sativa extract with high content of cannabidiol. Phytomedicine 21 (5): 631-9, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

Preet A, Ganju RK, Groopman JE: Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits epithelial growth factor-induced lung cancer cell migration in vitro as well as its growth and metastasis in vivo. Oncogene 27 (3): 339-46, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

Zhu LX, Sharma S, Stolina M, et al.: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits antitumor immunity by a CB2 receptor-mediated, cytokine-dependent pathway. J Immunol 165 (1): 373-80, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

McKallip RJ, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol enhances breast cancer growth and metastasis by suppression of the antitumor immune response. J Immunol 174 (6): 3281-9, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

Massa F, Marsicano G, Hermann H, et al.: The endogenous cannabinoid system protects against colonic inflammation. J Clin Invest 113 (8): 1202-9, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

Patsos HA, Hicks DJ, Greenhough A, et al.: Cannabinoids and cancer: potential for colorectal cancer therapy. Biochem Soc Trans 33 (Pt 4): 712-4, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

Liu WM, Fowler DW, Dalgleish AG: Cannabis-derived substances in cancer therapy–an emerging anti-inflammatory role for the cannabinoids. Curr Clin Pharmacol 5 (4): 281-7, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

Malfitano AM, Ciaglia E, Gangemi G, et al.: Update on the endocannabinoid system as an anticancer target. Expert Opin Ther Targets 15 (3): 297-308, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Sarfaraz S, Adhami VM, Syed DN, et al.: Cannabinoids for cancer treatment: progress and promise. Cancer Res 68 (2): 339-42, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

Nabissi M, Morelli MB, Santoni M, et al.: Triggering of the TRPV2 channel by cannabidiol sensitizes glioblastoma cells to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Carcinogenesis 34 (1): 48-57, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

Marcu JP, Christian RT, Lau D, et al.: Cannabidiol enhances the inhibitory effects of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on human glioblastoma cell proliferation and survival. Mol Cancer Ther 9 (1): 180-9, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

Torres S, Lorente M, Rodríguez-Fornés F, et al.: A combined preclinical therapy of cannabinoids and temozolomide against glioma. Mol Cancer Ther 10 (1): 90-103, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Rocha FC, Dos Santos Júnior JG, Stefano SC, et al.: Systematic review of the literature on clinical and experimental trials on the antitumor effects of cannabinoids in gliomas. J Neurooncol 116 (1): 11-24, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G: The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 58 (3): 389-462, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

Darmani NA: Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and synthetic cannabinoids prevent emesis produced by the cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist/inverse agonist SR 141716A. Neuropsychopharmacology 24 (2): 198-203, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

Darmani NA: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol differentially suppresses cisplatin-induced emesis and indices of motor function via cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in the least shrew. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 69 (1-2): 239-49, 2001 May-Jun. [PUBMED Abstract]

Parker LA, Kwiatkowska M, Burton P, et al.: Effect of cannabinoids on lithium-induced vomiting in the Suncus murinus (house musk shrew). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171 (2): 156-61, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

Mechoulam R, Berry EM, Avraham Y, et al.: Endocannabinoids, feeding and suckling–from our perspective. Int J Obes (Lond) 30 (Suppl 1): S24-8, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

Fride E, Bregman T, Kirkham TC: Endocannabinoids and food intake: newborn suckling and appetite regulation in adulthood. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 230 (4): 225-34, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

Baker D, Pryce G, Giovannoni G, et al.: The therapeutic potential of cannabis. Lancet Neurol 2 (5): 291-8, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

Walker JM, Hohmann AG, Martin WJ, et al.: The neurobiology of cannabinoid analgesia. Life Sci 65 (6-7): 665-73, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

Meng ID, Manning BH, Martin WJ, et al.: An analgesia circuit activated by cannabinoids. Nature 395 (6700): 381-3, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

Walker JM, Huang SM, Strangman NM, et al.: Pain modulation by release of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 (21): 12198-203, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

Facci L, Dal Toso R, Romanello S, et al.: Mast cells express a peripheral cannabinoid receptor with differential sensitivity to anandamide and palmitoylethanolamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 (8): 3376-80, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

Ibrahim MM, Porreca F, Lai J, et al.: CB2 cannabinoid receptor activation produces antinociception by stimulating peripheral release of endogenous opioids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 (8): 3093-8, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

Richardson JD, Kilo S, Hargreaves KM: Cannabinoids reduce hyperalgesia and inflammation via interaction with peripheral CB1 receptors. Pain 75 (1): 111-9, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

Khasabova IA, Gielissen J, Chandiramani A, et al.: CB1 and CB2 receptor agonists promote analgesia through synergy in a murine model of tumor pain. Behav Pharmacol 22 (5-6): 607-16, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Ward SJ, McAllister SD, Kawamura R, et al.: Cannabidiol inhibits paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain through 5-HT(1A) receptors without diminishing nervous system function or chemotherapy efficacy. Br J Pharmacol 171 (3): 636-45, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

Rahn EJ, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG: Activation of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors suppresses neuropathic nociception evoked by the chemotherapeutic agent vincristine in rats. Br J Pharmacol 152 (5): 765-77, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

Khasabova IA, Khasabov S, Paz J, et al.: Cannabinoid type-1 receptor reduces pain and neurotoxicity produced by chemotherapy. J Neurosci 32 (20): 7091-101, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Campos AC, Guimarães FS: Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199 (2): 223-30, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Hallak JE: [Therapeutic use of the cannabinoids in psychiatry]. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 32 (Suppl 1): S56-66, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

Guimarães FS, Chiaretti TM, Graeff FG, et al.: Antianxiety effect of cannabidiol in the elevated plus-maze. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 100 (4): 558-9, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

Méndez-Díaz M, Caynas-Rojas S, Arteaga Santacruz V, et al.: Entopeduncular nucleus endocannabinoid system modulates sleep-waking cycle and mood in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 107: 29-35, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

Pava MJ, den Hartog CR, Blanco-Centurion C, et al.: Endocannabinoid modulation of cortical up-states and NREM sleep. PLoS One 9 (2): e88672, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

Human/Clinical Studies

READ MORE:

Cannabis Pharmacology

Cancer Risk

Patterns of Cannabis Use Among Cancer Patients

Cancer Treatment

Antiemetic EffectCannabinoids

Cannabis

Appetite StimulationCannabinoids

Cannabis

AnalgesiaCannabinoids

Cannabis

Anxiety and SleepCannabinoids

Cannabis

Symptom Management With Cannabidiol

Clinical Studies of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

Current Clinical Trials